[ planet-factor ]

John Benediktsson: Standard Deviation

Standard deviation is “a measure of the amount of variation of the values of a variable about its mean.”. It’s a useful measure from statistics, and std in the math.statistics vocabulary included with Factor.

I bumped into this – um, are they still called tweets? – today:

Word with the lowest standard deviation of letter position in the alphabet, for each length pic.twitter.com/caHYDDpyBx

— Adam Aaronson (@aaaronson) February 4, 2026

Of course, I wondered how that looks for the /usr/share/dict/words on my computer:

IN: scratchpad "/usr/share/dict/words" utf8 file-lines

[ length ] collect-by

[ [ std ] minimum-by ] assoc-map

sort-keys values

[ dup std "%s: %s\n" printf ] each

A: 0.0

aa: 0.0

aba: 0.5773502691896257

baba: 0.5773502691896257

abaca: 0.8944271909999159

bacaba: 0.816496580927726

deedeed: 0.5345224838248488

poroporo: 1.3093073414159542

susurrous: 1.9364916731037085

beefheaded: 1.9578900207451218

cabbagehead: 2.46429041972071

fiddledeedee: 2.424621182533032

promonopolist: 2.911075226502911

monogonoporous: 3.1830595551871363

prophototropism: 3.5023801430836525

philophilosophos: 3.855731664245668

sulphophosphorous: 4.227013964824759

chemicoengineering: 4.556472090169843

plutonometamorphism: 5.220293285659733

encephalomeningocele: 4.871776937249466

philosophicoreligious: 5.014740177478695

philosophicohistorical: 5.485320828241917

philosophicotheological: 5.2090678006509625

scientificophilosophical: 5.538894097749744

antidisestablishmentarianism: 6.7081053397123425

Interesting, both similar and different. Well, it’s pretty close and also pretty obvious we are using slightly different dictionaries. I’m not sure what deedeed or poroporo mean and they aren’t in the SCRABBLE Players Dictionary.

Anyway, fun!

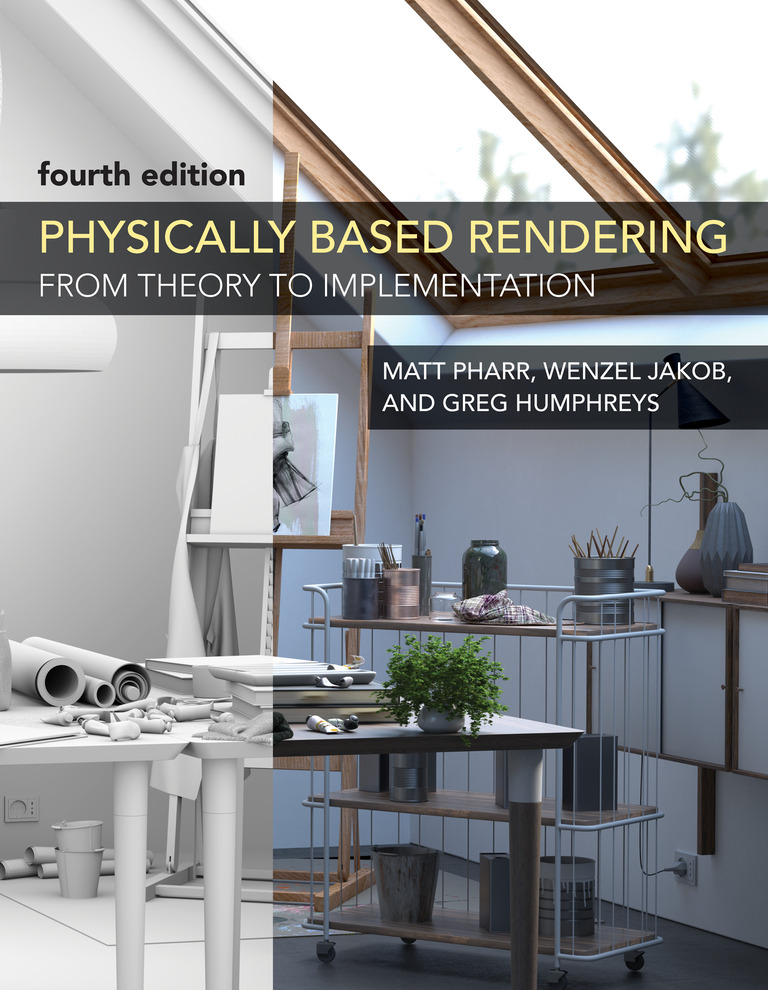

John Benediktsson: PBRT

PBRT is an impressive photorealistic rendering system:

From movies to video games, computer-rendered images are pervasive today. Physically Based Rendering introduces the concepts and theory of photorealistic rendering hand in hand with the source code for a sophisticated renderer.

The fourth edition of their book is now available on Amazon as well as freely available online.

I thought it would be fun to explore the PBRT v4 file format using Factor.

Here’s a short example pbrt file from their website:

LookAt 3 4 1.5 # eye

.5 .5 0 # look at point

0 0 1 # up vector

Camera "perspective" "float fov" 45

Sampler "halton" "integer pixelsamples" 128

Integrator "volpath"

Film "rgb" "string filename" "simple.png"

"integer xresolution" [400] "integer yresolution" [400]

WorldBegin

# uniform blue-ish illumination from all directions

LightSource "infinite" "rgb L" [ .4 .45 .5 ]

# approximate the sun

LightSource "distant" "point3 from" [ -30 40 100 ]

"blackbody L" 3000 "float scale" 1.5

AttributeBegin

Material "dielectric"

Shape "sphere" "float radius" 1

AttributeEnd

AttributeBegin

Texture "checks" "spectrum" "checkerboard"

"float uscale" [16] "float vscale" [16]

"rgb tex1" [.1 .1 .1] "rgb tex2" [.8 .8 .8]

Material "diffuse" "texture reflectance" "checks"

Translate 0 0 -1

Shape "bilinearmesh"

"point3 P" [ -20 -20 0 20 -20 0 -20 20 0 20 20 0 ]

"point2 uv" [ 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 ]

AttributeEnd

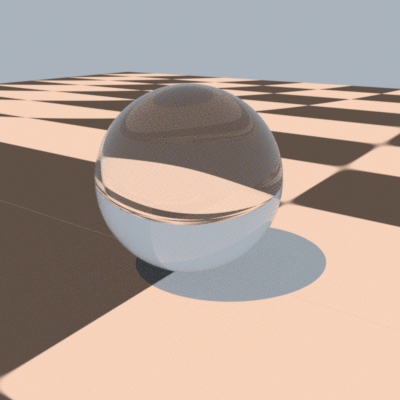

And this is what it might look like:

Using our new pbrt vocabulary, we can convert that text into a set of tuples that we could do computations on, or potentially look into rendering or processing. And, of course, it also supports round-tripping back and forth from text to tuples.

{

T{ pbrt-look-at

{ eye-x 3 }

{ eye-y 4 }

{ eye-z 1.5 }

{ look-x 0.5 }

{ look-y 0.5 }

{ look-z 0 }

{ up-x 0 }

{ up-y 0 }

{ up-z 1 }

}

T{ pbrt-camera

{ type "perspective" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "float" }

{ name "fov" }

{ values { 45 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-sampler

{ type "halton" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "integer" }

{ name "pixelsamples" }

{ values { 128 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-integrator { type "volpath" } { params { } } }

T{ pbrt-film

{ type "rgb" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "string" }

{ name "filename" }

{ values { "simple.png" } }

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "integer" }

{ name "xresolution" }

{ values { 400 } }

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "integer" }

{ name "yresolution" }

{ values { 400 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-world-begin }

T{ pbrt-light-source

{ type "infinite" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "rgb" }

{ name "L" }

{ values { 0.4 0.45 0.5 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-light-source

{ type "distant" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "point3" }

{ name "from" }

{ values { -30 40 100 } }

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "blackbody" }

{ name "L" }

{ values { 3000 } }

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "float" }

{ name "scale" }

{ values { 1.5 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-attribute-begin }

T{ pbrt-material { type "dielectric" } { params { } } }

T{ pbrt-shape

{ type "sphere" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "float" }

{ name "radius" }

{ values { 1 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-attribute-end }

T{ pbrt-attribute-begin }

T{ pbrt-texture

{ name "checks" }

{ value-type "spectrum" }

{ class "checkerboard" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "float" }

{ name "uscale" }

{ values { 16 } }

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "float" }

{ name "vscale" }

{ values { 16 } }

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "rgb" }

{ name "tex1" }

{ values { 0.1 0.1 0.1 } }

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "rgb" }

{ name "tex2" }

{ values { 0.8 0.8 0.8 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-material

{ type "diffuse" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "texture" }

{ name "reflectance" }

{ values { "checks" } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-translate { x 0 } { y 0 } { z -1 } }

T{ pbrt-shape

{ type "bilinearmesh" }

{ params

{

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "point3" }

{ name "P" }

{ values

{ -20 -20 0 20 -20 0 -20 20 0 20 20 0 }

}

}

T{ pbrt-param

{ type "point2" }

{ name "uv" }

{ values { 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 } }

}

}

}

}

T{ pbrt-attribute-end }

}

This is available now in the development version of Factor!

John Benediktsson: Migrating to GTK3

Factor has a native ui-backend that allows us to render our UI framework using OpenGL on top of platform-specific APIs for our primary targets of Linux, macOS, and Windows.

On Linux, for a long time that has meant using the

GTK2 library, which has also meant using

X11 and an old library

called libgtkglext which provides a way to use OpenGL within GTK

windows. Well, Linux has moved on and is now pushing

Wayland as the “replacement for the X11

window system protocol and architecture with the aim to be easier to

develop, extend, and maintain”. Most modern Linux distributions have moved

to GTK3 or GTK4 and abstraction libraries like

libepoxy for working with OpenGL and

others for supporting both X11 and Wayland renderers.

I was reminded of this after our recent Factor 0.101 release when someone asked the question:

Does that message mean that Factor still relies on GTK2? IIRC it was EOL:ed around 2020.

Well, this is embarassing – yeah it sure does! Or rather – yes it sure did.

I got motivated to look into what it would take to support GTK3 or GTK4. We had a pull request that was working through adding support for GTK4. After merging that, and modifying it to also provide GTK3 support, I re-discovered that our OpenGL rendering was generally using OpenGL 1.x pipelines and that would not work in a GTK3+ world.

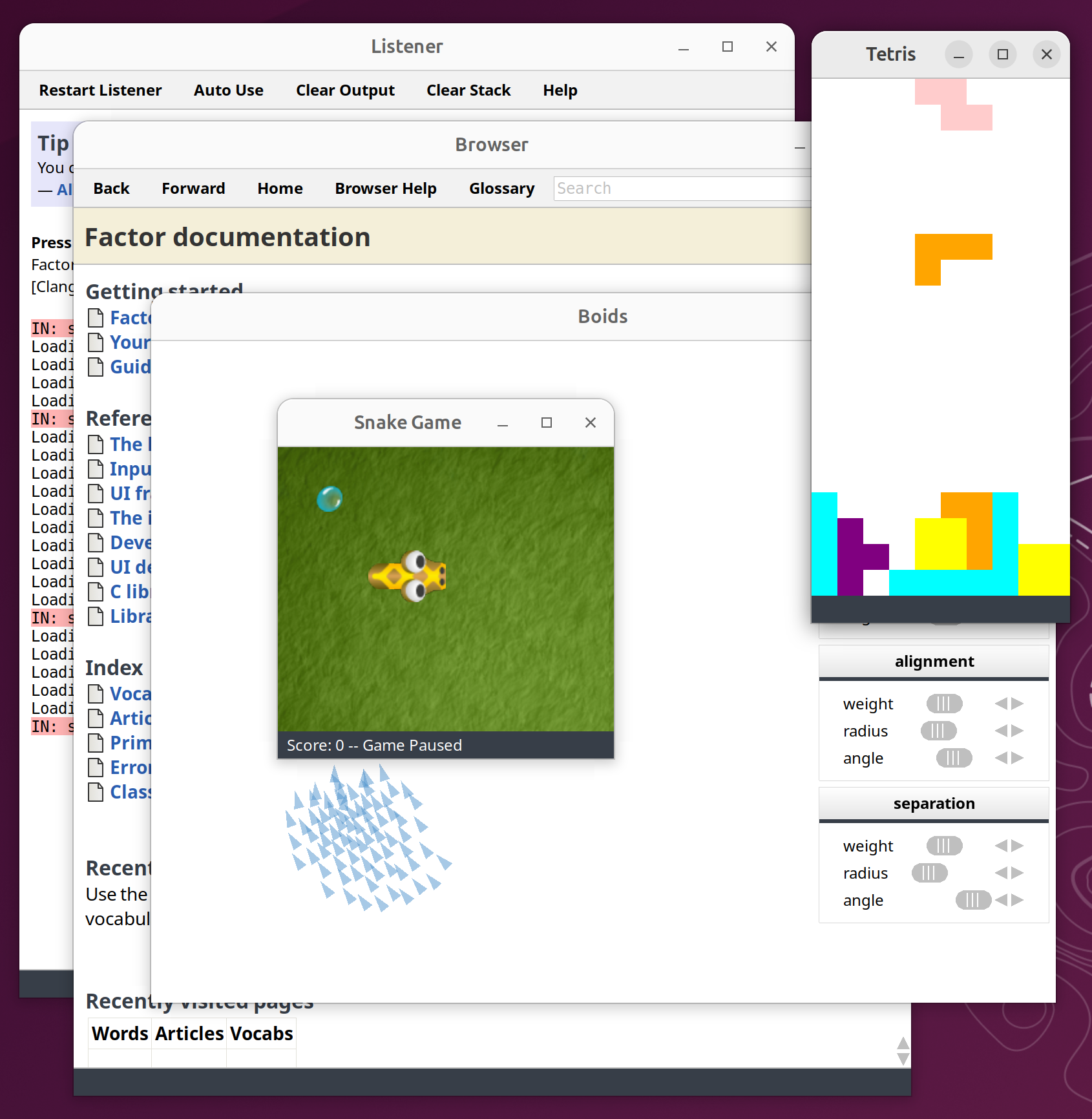

So, after adding OpenGL 3.x support for most of the things our user interface needs, and migrating from GTK 2.x to GTK3, we now have experimental nightly builds using the GTK3 backend:

You can revert to the older GTK2 backend by applying this diff and then performing a fresh bootstrap:

diff --git a/basis/bootstrap/ui/ui.factor b/basis/bootstrap/ui/ui.factor

index 2974e530f9..416704ce29 100644

--- a/basis/bootstrap/ui/ui.factor

+++ b/basis/bootstrap/ui/ui.factor

@@ -12,6 +12,6 @@ IN: bootstrap.ui

{

{ [ os macos? ] [ "ui.backend.cocoa" ] }

{ [ os windows? ] [ "ui.backend.windows" ] }

- { [ os unix? ] [ "ui.backend.gtk3" ] }

+ { [ os unix? ] [ "ui.backend.gtk2" ] }

} cond

] if* require

diff --git a/basis/opengl/gl/extensions/extensions.factor b/basis/opengl/gl/extensions/extensions.factor

index 2d408e93bb..51394eeb4a 100644

--- a/basis/opengl/gl/extensions/extensions.factor

+++ b/basis/opengl/gl/extensions/extensions.factor

@@ -7,7 +7,7 @@ ERROR: unknown-gl-platform ;

<< {

{ [ os windows? ] [ "opengl.gl.windows" ] }

{ [ os macos? ] [ "opengl.gl.macos" ] }

- { [ os unix? ] [ "opengl.gl.gtk3" ] }

+ { [ os unix? ] [ "opengl.gl.gtk2" ] }

[ unknown-gl-platform ]

} cond use-vocab >>

It seems like the newer OpenGL 3.x functions might introduce some lag which is visible when scrolling on some installations, perhaps by not caching certain things that were cached in the OpenGL 1.x code paths. There will need to be some improvements before we are ready to release it, but it is plenty usable as-is.

I also migrated our macOS backend to use the OpenGL 3.x functions as well to allow us to more broadly test and improve these new rendering paths.

This is available in the latest development version.

John Benediktsson: DNS LOC Records

DNS is the Domain Name System and is the backbone of the internet:

Most prominently, it translates readily memorized domain names to the numerical IP addresses needed for locating and identifying computer services and devices with the underlying network protocols. The Domain Name System has been an essential component of the functionality of the Internet since 1985.

It is also an oft-cited reason for service outages, with a funny decade-old r/sysadmin meme:

Factor has a DNS vocabulary that supports querying and parsing responses from nameservers:

IN: scratchpad USE: tools.dns

IN: scratchpad "google.com" host

google.com has address 142.250.142.113

google.com has address 142.250.142.138

google.com has address 142.250.142.100

google.com has address 142.250.142.101

google.com has address 142.250.142.102

google.com has address 142.250.142.139

google.com has IPv6 address 2607:f8b0:4023:1c01:0:0:0:8b

google.com has IPv6 address 2607:f8b0:4023:1c01:0:0:0:8a

google.com has IPv6 address 2607:f8b0:4023:1c01:0:0:0:64

google.com has IPv6 address 2607:f8b0:4023:1c01:0:0:0:65

google.com mail is handled by 10 smtp.google.com

Recently, I bumped into an old post on the Cloudflare

blog about The weird and wonderful world of

DNS LOC

records

and realized that we did not properly support parsing RFC

1876 which specifies a format

for returning LOC or location record specifying the physical

location of a service.

At the time of the post, Cloudflare indicated they handle “millions of DNS records; of those just 743 are LOCs.”. I found a webpage that lists sites supporting DNS LOC and contains only nine examples.

It is not widely used, but it is very cool.

You can use the dig command

to query for a LOC record and see what is returned:

$ dig alink.net LOC

alink.net. 66 IN LOC 37 22 26.000 N 122 1 47.000 W 30.00m 30m 30m 10m

The fields that were returned include:

- latitude (37° 22’ 26.00" N)

- longitude (122° 1’ 47.00" W)

- altitude (30.00m)

- horizontal precision (30m)

- vertical precision (30m)

- entity size estimate (10m)

In Factor 0.101, the field is available and returned as bytes but not parsed:

IN: scratchpad "alink.net" dns-LOC-query answer-section>> ...

{

T{ rr

{ name "alink.net" }

{ type LOC }

{ class IN }

{ ttl 300 }

{ rdata

B{

0 51 51 19 136 5 2 80 101 208 181 8 0 152 162 56

}

}

}

}

Of course, I love odd uses of technology like Wikipedia over

DNS and I thought

Factor should probably add proper support for the

LOC record!

First, we define a tuple

class to hold the

LOC record fields:

TUPLE: loc size horizontal vertical lat lon alt ;

Next, we parse the LOC record, converting sizes (in centimeters),

lat/lon (in degrees), and altitude (in centimeters):

: parse-loc ( -- loc )

loc new

read1 0 assert=

read1 [ -4 shift ] [ 4 bits ] bi 10^ * >>size

read1 [ -4 shift ] [ 4 bits ] bi 10^ * >>horizontal

read1 [ -4 shift ] [ 4 bits ] bi 10^ * >>vertical

4 read be> 31 2^ - 3600000 / >>lat

4 read be> 31 2^ - 3600000 / >>lon

4 read be> 10000000 - >>alt ;

We hookup the LOC type to be parsed properly:

M: LOC parse-rdata 2drop parse-loc ;

And then build a word to print the location nicely:

: LOC. ( name -- )

dns-LOC-query answer-section>> [

rdata>> {

[ lat>> [ abs 1 /mod 60 * 1 /mod 60 * ] [ neg? "S" "N" ? ] bi ]

[ lon>> [ abs 1 /mod 60 * 1 /mod 60 * ] [ neg? "W" "E" ? ] bi ]

[ alt>> 100 / ]

[ size>> 100 /i ]

[ horizontal>> 100 /i ]

[ vertical>> 100 /i ]

} cleave "%d %d %.3f %s %d %d %.3f %s %.2fm %dm %dm %dm\n" printf

] each ;

And, finally, we can give it a try!

IN: scratchpad "alink.net" LOC.

37 22 26.000 N 122 1 47.000 W 30.00m 30m 30m 10m

Yay, it matches!

This is available in the latest development version.

John Benediktsson: Factor 0.101 now available

“Keep thy airspeed up, lest the earth come from below and smite thee.” - William Kershner

I’m very pleased to announce the release of Factor 0.101!

| OS/CPU | Windows | Mac OS | Linux |

|---|---|---|---|

| x86 | 0.101 | 0.101 | |

| x86-64 | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.101 |

Source code: 0.101

This release is brought to you with almost 700 commits by the following individuals:

Aleksander Sabak, Andy Kluger, Cat Stevens, Dmitry Matveyev, Doug Coleman, Giftpflanze, John Benediktsson, Jon Harper, Jonas Bernouli, Leo Mehraban, Mike Stevenson, Nicholas Chandoke, Niklas Larsson, Rebecca Kelly, Samuel Tardieu, Stefan Schmiedl, @Bruno-366, @bobisageek, @coltsingleactionarmyocelot, @inivekin, @knottio, @timor

Besides some bug fixes and library improvements, I want to highlight the following changes:

- Moved the UI to render buttons and scrollbars rather than using images, which allows easier theming.

- Fixed HiDPI scaling on Linux and Windows, although it currently doesn’t update the window settings when switching between screens with different scaling factors.

- Update to Unicode 17.0.0.

- Plugin support for the Neovim editor.

Some possible backwards compatibility issues:

- The argument order to

ltakewas swapped to be more consistent with words likehead. - The

environmentvocabulary on Windows now supports disambiguatingfand""(empty) values - The

misc/atomfolder was removed in favor of the factor/atom-language-factor repo. - The

misc/Factor.tmbundlefolder was removed in favor of the factor/factor.tmbundle repo. - The

misc/vimfolder was removed in favor of the factor/factor.vim repo. - The

httpvocabularyrequesttuple had a slot rename frompost-datatodata. - The

furnace.asidesvocabulary had a slot rename frompost-datatodata, and might require runningALTER TABLE asides RENAME COLUMN "post-data" TO data;. - The

html.streamsvocabulary was renamed toio.streams.html - The

pdf.streamsvocabulary was renamed toio.streams.pdf

What is Factor

Factor is a concatenative, stack-based programming language with high-level features including dynamic types, extensible syntax, macros, and garbage collection. On a practical side, Factor has a full-featured library, supports many different platforms, and has been extensively documented.

The implementation is fully compiled for performance, while still supporting interactive development. Factor applications are portable between all common platforms. Factor can deploy stand-alone applications on all platforms. Full source code for the Factor project is available under a BSD license.

New libraries:

- base92: adding support for Base92 encoding/decoding

- bitcask: implementing the Bitcask key/value database

- bluesky: adding support for the BlueSky protocol

- calendar.holidays.world: adding some new holidays including World Emoji Day

- classes.enumeration: adding enumeration classes and new

ENUMERATION:syntax word - colors.oklab: adding support for OKLAB color space

- colors.oklch: adding support for OKLCH color space

- colors.wavelength: adding

wavelength>rgba - combinators.syntax: adding experimental combinator syntax words

@[,*[, and&[, and short-circuitingn&&[,n||[,&&[and||[ - continuations.extras: adding

with-datastacksanddatastack-states - dotenv: implementing support for Dotenv files

- edn: implementing support for Extensible Data Notation

- editors.cursor: adding support for the Cursor editor

- editors.rider: adding support for the JetBrains Rider editor

- gitignore: parser for

.gitignorefiles - http.json: promoted

json.httpand added some useful words - io.streams.farkup: a Farkup formatted stream protocol

- io.streams.markdowns: a Markdown formatted stream protocol

- locals.lazy: prototype of emit syntax

- monadics: alternative vocabulary for using Haskell-style monads, applicatives, and functors

- multibase: implementation of Multibase

- pickle: support for the Pickle serialization format

- persistent.hashtables.identity: support an identity-hashcode version of persisent hashtables

- raylib.live-coding: demo of a vocabulary to do “live coding” of Raylib programs

- rdap: support for the Registration Data Access Protocol

- reverse: implementation of the std::flip

- slides.cli: simple text-based command-line interface for slides

- tools.highlight: command-line syntax-highlighting tool

- tools.random: command-line random generator tool

- ui.pens.rounded: adding rounded corner pen

- ui.pens.theme: experimental themed pen

- ui.tools.theme: some words for updating UI developer tools themes

Improved libraries:

- alien.syntax: added

C-LIBRARY:syntax word - assocs.extras: added

nzipandnunzip,map-zipandmap-unzipmacros - base32: adding the human-oriented Base32 encoding via

zbase32>and>zbase32 - base64: minor performance improvement

- benchmark: adding more benchmarks

- bootstrap.assembler: fixes for ARM-64

- brainfuck: added

BRAINFUCK:syntax word andinterpret-brainfuck - bson: use linked-assocs to preserve order

- cache: implement

M\ cache-assoc delete-at - calendar: adding

year<,year<=,year>,year>=words - calendar.format: parse human-readable and elapsed-time output back into duration objects

- cbor: use linked-assocs to preserve order

- classes.mixin: added

definerimplementation - classes.singleton: added

definerimplementation - classes.tuple: added

tuple>slots, renametuple>arraytopack-tupleand>tupletounpack-tuple. - classes.union: added

definerimplementation - checksums.sha: some 20-40% performance improvements

- command-line: allow passing script name of

-to use stdin - command-line.parser: support for Argument Parser Commands

- command-line.startup: document

-qquiet mode flag - concurrency.combinators: faster

parallel-mapandparallel-assoc-mapusing a count-down latch - concurrency.promises: 5-7% performance improvement

- continuations: improve docs and fix stack effect for

ifcc - countries: adding

CQcountry code for Sark - cpu.architecture: fix

*-branchstack effects - cpu.arm: fixes for ARM-64

- crontab: added

parse-crontabwhich ignores blank lines and comments - db: making

query-eachrow-polymorphic - delegate.protocols: adding

keysandvaluestoassoc-protocol - discord: better support for network disconnects, added a configurable retry interval

- discord.chatgpt-bot: some fixes for LM Studio

- editors: make the editor restart nicer looking

- editors.focus: support open-file-to-line-number on newer releases, support Linux and Window

- editors.zed: support use of Zed on Linux

- endian: faster endian conversions of c-ptr-like objects

- environment: adding

os-env? - eval: move datastack and error messages to stderr

- fonts: make

<font>take a name, easier defaults - furnace.asides: rename

post-dataslot onasidetuples todata - generalizations: moved some dip words to shuffle

- help.tour: fix some typos/grammar

- html.templates.chloe: improve use of

CDATAtags for unescaping output - http: rename

post-dataslot onrequesttuples todata - http.json: adding

http-jsonthat doesn’t return the response object - http.websockets: making

read-websocket-looprow-polymorphic - ini-file: adding

ini>file,file>ini, and useLH{ }to preserve configuration order - io.encodings.detect: adding

utf7detection - io.encodings.utf8: adding

utf8-bomto handle optional BOM - io.random: speed up

random-lineandrandom-lines - io.streams.ansi: adding documentation and tests, support dim foreground on terminals that support it

- io.streams.escape-codes: adding documentation and tests

- ip-parser: adding IPV4 and IPV6 network words

- kernel: adding

until*, fix docs forand*andor* - linked-sets: adding

LS{syntax word - lists.lazy: changed the argument order in

ltake - macho: support a few more link edit commands

- make: adding

,%for apush-atvariant - mason.release.tidy: cleanup a few more git artifacts

- math.combinatorics: adding counting words

- math.distances: adding

jaro-distanceandjaro-winkler-distance - math.extras: added

all-removals, support Recamán’s sequence, and Tribonacci Numbers - math.factorials: added

subfactorial - math.functions: added “closest to zero” modulus

- math.parser: improve ratio parsing for consistency

- math.primes: make

prime?safe from non-integer inputs - math.runge-kutta: make generalized improvements to the Runge-Kutta solver

- math.similarity: adding

jaro-similarity,jaro-winkler-similarity, andtrigram-similarity - math.text.english: fix issue with very large and very small floats

- metar: updated the abbreviations glossary

- mime.types: updating

mime.typesfile - msgpack: use linked-assocs to preserve order

- qw: adding

qw:syntax - path-finding: added

find-path* - peg.parsers: faster

list-ofandlist-of-many - progress-bars.models: added

with-progress-display,map-with-progress-bar,each-with-progress-bar, andreduce-with-progress-bar - raylib: adding

trace-logandset-trace-log-level, updated to Raylib 5.5 - readline-listener: store history across sessions, support color on terminals that support it

- robohash: support for

"set4","set5", and"set6"types - sequences: rename

midpoint@tomidpoint, fastereach-fromandmap-reduceon slices - sequences.extras: adding

find-nth,find-nth-last,subseq-indices,deep-nth,deep-nth-of,2none?,filter-errors,reject-errors,all-same?,adjacent-differences, andpartial-sum. - sequences.generalizations: fix

?firstnand?lastnfor string inputs, removed(nsequence)which duplicatesset-firstn-unsafe - sequences.prefixed: swap order of

<prefixed>arguments to matchprefix - sequences.repeating: adding

<cycles-from>andcycle-from - sequences.snipped: fixed out-of-bounds issues

- scryfall: update for duskmourn

- shuffle: improve stack-checking of

shuffle(syntax, addedSHUFFLE:syntax,nreverse - sorting: fix

sort-withto apply the quot with access to the stack below - sorting.human: implement human sorting improved

- system-info.macos: adding “Tahoe” code-name for macOS 26

- terminfo: add words for querying specific output capabilities

- threads: define a generalized

linked-threadwhich used to be forconcurrency.mailboxesonly - toml: use linked-assocs to preserve order, adding

>tomlandwrite-toml - tools.annotations: adding

<WATCH ... WATCH>syntax - tools.deploy: adding a command-line interface for deploy options

- tools.deploy.backend: fix boot image location in system-wide installations

- tools.deploy.unix: change binary name to append

.outto fix conflict with vocab resources - tools.directory-to-file: better test file metrics, print filename for editing

- tools.memory: adding

heap-stats-ofarbitrary sequence of instances, andtotal-sizesize of everything pointed to by an object - txon: use linked-assocs to preserve order

- ui: adding

adjust-font-size - ui.gadgets.buttons: stop using images and respect theme colors

- ui.gadgets.sliders: stop using images and respect theme colors

- ui.theme.base16: adding a lot more (270!) Base16 Themes

- ui.tools: adding font-sizing keyboard shortcuts

- ui.tools.browser: more responsive font sizing

- ui.tools.listener: more responsive font sizing, adding some UI listener styling

- ui.tools.listener.completion: allow spaces in history search popup

- unicode: update to Unicode 17.0.0

- webapps.planet: improve CSS for

videotags - words: adding

define-temp-syntax - zoneinfo: update to version 2025b

Removed libraries

ui.theme.images

VM Improvements:

- More work on ARM64 backend (fix set-callstack, fix generic dispatch)

John Benediktsson: zxcvbn

Years ago, Dropbox wrote about zxcvbn: realistic password strength estimation:

zxcvbnis a password strength estimator inspired by password crackers. Through pattern matching and conservative estimation, it recognizes and weighs 30k common passwords, common names and surnames according to US census data, popular English words from Wikipedia and US television and movies, and other common patterns like dates, repeats (aaa), sequences (abcd), keyboard patterns (qwertyuiop), and l33t speak.

And it appears to have been successful – the original implementation is in JavaScript, but there have been clones of the algorithm generated in many different languages:

At Dropbox we use zxcvbn (Release notes) on our web, desktop, iOS and Android clients. If JavaScript doesn’t work for you, others have graciously ported the library to these languages:

zxcvbn-python(Python)zxcvbn-cpp(C/C++/Python/JS)zxcvbn-c(C/C++)zxcvbn-rs(Rust)zxcvbn-go(Go)zxcvbn4j(Java)nbvcxz(Java)zxcvbn-ruby(Ruby)zxcvbn-js(Ruby [via ExecJS])zxcvbn-ios(Objective-C)zxcvbn-cs(C#/.NET)szxcvbn(Scala)zxcvbn-php(PHP)zxcvbn-api(REST)ocaml-zxcvbn(OCaml bindings forzxcvbn-c)

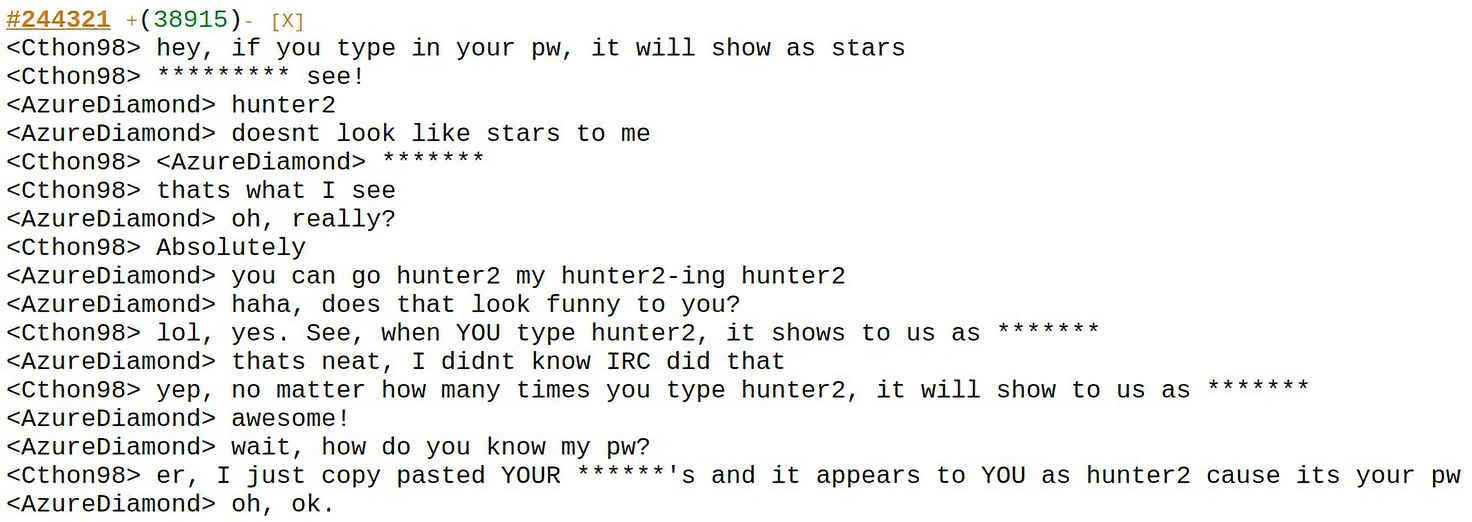

In today’s era of password managers, WebAuthn also known as passkeys, and many pwned accounts, passwords may seem like a funny sort of outdated concept. They have definitely provided good entertainment over the years from XKCD: Password Strength comics to the 20-year old hunter2 meme:

I have wanted a Factor implementation of this for a long time – and finally built zxcvbn in Factor!

We can use it to check out some potential passwords:

IN: scratchpad USE: zxcvbn

IN: scratchpad "F@ct0r!" zxcvbn.

Score:

1/4 (very guessable)

Crack times:

Online (throttled): 4 months

Online (unthrottled): 8 hours

Offline (slow hash): 30 seconds

Offline (fast hash): less than a second

Suggestions:

Add another word or two. Uncommon words are better.

Capitalization doesn't help very much.

Predictable substitutions like '@' instead of 'a' don't help very much.

IN: scratchpad "john2025" zxcvbn.

Score:

1/4 (very guessable)

Crack times:

Online (throttled): 3 months

Online (unthrottled): 6 hours

Offline (slow hash): 23 seconds

Offline (fast hash): less than a second

Warning:

Common names and surnames are easy to guess.

Suggestions:

Add another word or two. Uncommon words are better.

That’s not so good, maybe we should use the random.passwords vocabulary instead!

This is available on my GitHub.

John Benediktsson: AsyncIO Performance

Factor has green threads and a long-standing feature request to be able to utilize native threads more efficiently for concurrent tasks. In the meantime, the cooperative threading model allows for asynchronous tasks which is particularly useful when waiting for I/O such as used by sockets over a computer network.

And while it might be true that asynchrony is not concurrency, there are a lot of other things one could say about concurrency and multi-threaded or multi-process performance. Today I want to discuss an article that Will McGugan wrote about the overhead of Python asyncio tasks and the good discussion that followed on Hacker News.

Let’s go over the benchmark in a few programming languages – including Factor!

Python

The article presents this benchmark in Python that does no work but measures the relative overhead of the asyncio task infrastructure when creating a large number of asynchronous tasks:

from asyncio import create_task, wait, run

from time import process_time as time

async def time_tasks(count=100) -> float:

"""Time creating and destroying tasks."""

async def nop_task() -> None:

"""Do nothing task."""

pass

start = time()

tasks = [create_task(nop_task()) for _ in range(count)]

await wait(tasks)

elapsed = time() - start

return elapsed

for count in range(100_000, 1_000_000 + 1, 100_000):

create_time = run(time_tasks(count))

create_per_second = 1 / (create_time / count)

print(f"{count:9,} tasks \t {create_per_second:0,.0f} tasks per/s")

Using the latest Python 3.14, this is reasonably fast on my laptop taking about 13 seconds:

$ time python3.14 foo.py

100,000 tasks 577,247 tasks per/s

200,000 tasks 533,911 tasks per/s

300,000 tasks 546,127 tasks per/s

400,000 tasks 488,219 tasks per/s

500,000 tasks 466,636 tasks per/s

600,000 tasks 469,972 tasks per/s

700,000 tasks 434,126 tasks per/s

800,000 tasks 428,456 tasks per/s

900,000 tasks 404,905 tasks per/s

1,000,000 tasks 376,167 tasks per/s

python3.14 foo.py 12.69s user 0.27s system 99% cpu 12.971 total

Factor

We could translate this directly to Factor using the concurrency.combinators vocabulary.

In particular, the parallel-map word starts a new thread applying a quotation to each element in the sequence and then waits for all the threads to finish:

USING: concurrency.combinators formatting io kernel math ranges sequences

tools.time ;

: time-tasks ( n -- )

<iota> [ ] parallel-map drop ;

: run-tasks ( -- )

100,000 1,000,000 100,000 <range> [

dup [ time-tasks ] benchmark 1e9 / dupd /

"%7d tasks \t %7d tasks per/s\n" printf flush

] each ;

After making an improvement to our parallel-map implementation that uses a count-down latch for more efficient waiting on a group of tasks, this runs 2.5x as fast as Python:

IN: scratchpad gc [ run-tasks ] time

100000 tasks 1246872 tasks per/s

200000 tasks 1209500 tasks per/s

300000 tasks 1141121 tasks per/s

400000 tasks 1121304 tasks per/s

500000 tasks 1119707 tasks per/s

600000 tasks 1135459 tasks per/s

700000 tasks 956541 tasks per/s

800000 tasks 1091807 tasks per/s

900000 tasks 944753 tasks per/s

1000000 tasks 1137681 tasks per/s

Running time: 5.142044833 seconds

That’s pretty good for a comparable dynamic language, and especially since we are still running in Rosetta 2 on Apple macOS translating Intel x86-64 to Apple Silicon aarch64 on the fly!

It also turns out that 75% of the benchmark time is spent in the garbage collector, so probably there are some big wins we can get if we look more closely into that.

Go

We could translate that benchmark into Go 1.25:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

)

func timeTasks(count int) time.Duration {

nopTask := func(done func()) {

done()

}

start := time.Now()

wg := &sync.WaitGroup{}

wg.Add(count)

for i := 0; i < count; i++ {

go nopTask(wg.Done)

}

wg.Wait()

return time.Now().Sub(start)

}

func main() {

for n := 100_000; n <= 1_000_000; n += 100_000 {

createTime := timeTasks(n)

createPerSecond := (1.0 / (float64(createTime) / float64(n))) * float64(time.Second)

fmt.Printf("%7d tasks \t %7d tasks per/s\n", n, createPerSecond)

}

}

And show that it is about 11x times faster than Python using multiple CPUs.

$ time go run foo.go

100000 tasks 3889083 tasks per/s

200000 tasks 5748283 tasks per/s

300000 tasks 6324955 tasks per/s

400000 tasks 6265341 tasks per/s

500000 tasks 6301852 tasks per/s

600000 tasks 5572898 tasks per/s

700000 tasks 6239860 tasks per/s

800000 tasks 6276241 tasks per/s

900000 tasks 6226128 tasks per/s

1000000 tasks 6243859 tasks per/s

go run foo.go 2.44s user 0.71s system 270% cpu 1.165 total

If we limit GOMAXPROCS to one CPU, it runs only 7.5x times faster than Python:

$ time GOMAXPROCS=1 go run foo.go

100000 tasks 2240106 tasks per/s

200000 tasks 2869379 tasks per/s

300000 tasks 2745897 tasks per/s

400000 tasks 3759142 tasks per/s

500000 tasks 3090267 tasks per/s

600000 tasks 3489138 tasks per/s

700000 tasks 3608874 tasks per/s

800000 tasks 3200636 tasks per/s

900000 tasks 3682102 tasks per/s

1000000 tasks 3259778 tasks per/s

GOMAXPROCS=1 go run foo.go 1.65s user 0.08s system 99% cpu 1.735 total

JavaScript

We could build the same benchmark in JavaScript:

async function time_tasks(count=100) {

async function nop_task() {

return performance.now();

}

const start = performance.now()

let tasks = Array(count).map(nop_task)

await Promise.all(tasks)

const elapsed = performance.now() - start

return elapsed / 1e3

}

async function run_tasks() {

for (let count = 100000; count < 1000000 + 1; count += 100000) {

const ct = await time_tasks(count)

console.log(`${count}: ${Math.round(1 / (ct / count))} tasks/sec`)

}

}

run_tasks()

And it runs pretty fast on Node 25.2.1 – about 26x times faster than Python!

$ time node foo.js

100000: 9448038 tasks/sec

200000: 11555322 tasks/sec

300000: 18286318 tasks/sec

400000: 10017217 tasks/sec

500000: 12587060 tasks/sec

600000: 14198956 tasks/sec

700000: 13294620 tasks/sec

800000: 12045403 tasks/sec

900000: 11135513 tasks/sec

1000000: 13577663 tasks/sec

node foo.js 0.82s user 0.10s system 185% cpu 0.496 total

But it runs even faster on Bun 1.3.3 – about 36x times faster than Python!

$ time bun foo.js

100000: 9771222 tasks/sec

200000: 13388075 tasks/sec

300000: 13242548 tasks/sec

400000: 13130144 tasks/sec

500000: 16530496 tasks/sec

600000: 16979009 tasks/sec

700000: 16781272 tasks/sec

800000: 17098919 tasks/sec

900000: 17111784 tasks/sec

1000000: 18288515 tasks/sec

bun foo.js 0.37s user 0.02s system 111% cpu 0.353 total

I’m sure other languages perform both better and worse, but this gives us some nice ideas of where we stand relative to some useful production programming languages. There is clearly room to grow, some potential low-hanging fruit, and known features such as supporting native threads that could be a big improvement to the status quo!

PRs welcome!

John Benediktsson: Cosine FizzBuzz

After revisiting FizzBuzz yesterday to discuss a Lazy FizzBuzz using infinite lazy lists, I thought I would not return to the subject for awhile. Apparently, I was wrong!

Susam Pal just wrote a really fun article about Solving Fizz Buzz with Cosines:

We define a set of four functions {

s0,s1,s2,s3} for integersnby:

s0(n) = n

s1(n) = Fizz

s2(n) = Buzz

s3(n) = FizzBuzz

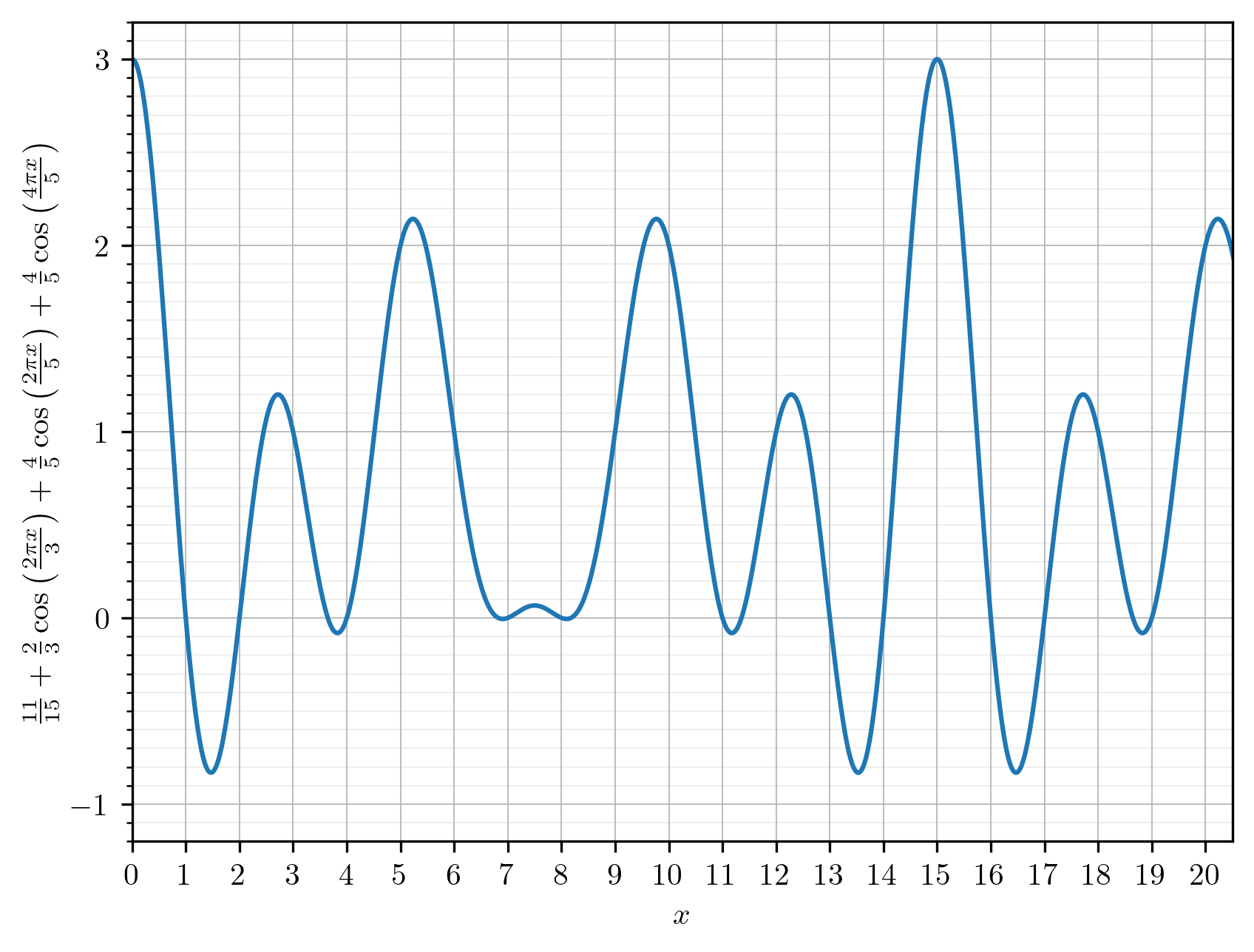

And from that, they derive a formula which is essentially a finite Fourier

series for computing the nth

value in the FizzBuzz sequence, showing a nice fixed periodic cycling across

n mod 15, resolving at each value of n to either the integers 0, 1, 2, 3:

I recommend reading the whole article, but I will jump to an implementation of the formula in Factor:

:: fizzbuzz ( n -- val )

11/15

2/3 n * pi * cos 2/3 * +

2/5 n * pi * cos 4/5 * +

4/5 n * pi * cos + round >integer

{ n "Fizz" "Buzz" "FizzBuzz" } nth ;

And we can use that to compute the first few values in the sequence:

IN: scratchpad 1 ..= 100 [ fizzbuzz . ] each

1

2

"Fizz"

4

"Buzz"

"Fizz"

7

8

"Fizz"

"Buzz"

11

"Fizz"

13

14

"FizzBuzz"

16

17

"Fizz"

19

"Buzz"

...

Or, even some arbitrary values in the sequence:

IN: scratchpad 67 fizzbuzz .

67

IN: scratchpad 9,999,999 fizzbuzz .

"Fizz"

IN: scratchpad 10,000,000 fizzbuzz .

"Buzz"

IN: scratchpad 1,234,567,890 fizzbuzz .

"FizzBuzz"

Thats even more fun than using lazy lists!

Blogroll

- Chris Double

- Daniel Ehrenberg

- Doug Coleman

- Jeremy Hughes

- Joe Groff

- John Benediktsson

- Phil Dawes

- Samuel Tardieu

- Slava Pestov

planet-factor is an Atom/RSS aggregator that collects the contents of Factor-related blogs. It is inspired by Planet Lisp.